The River Maigue and its tributaries support a great variety of fish species. Seventeen fish species have been recorded from the rivers of the Maigue catchment. Six of these are confined to the tidal estuary of the Maigue, four to the freshwater reaches (Table 1). To see images and descriptions of some of the fish mentioned, look up the Inland Fisheries Ireland webpage http://www.fisheriesireland.ie/Research-and-Development/fish-species.html.

Salmon

Atlantic Salmon are the most iconic of the Maigue fish. Salmon spend one more years feeding at sea before returning to spawn in the rivers where they were born. Young salmon grow to juveniles for a year or more before migrating to sea again as smolts. Salmon returning to their home river after two or more years at sea mostly return in spring or early summer and are bigger than salmon that return in mid-summer and autumn; these latter are known as grilse or peel. The majority of salmon returning to the Maigue are spring salmon. Most of the salmon die after spawning but a number may return to the sea (as kelts) in spring and may return to spawn a second or even a third time. Most of these are hen fish.

Sadly, the numbers of returning salmon have declined drastically in recent years in all Irish rivers including the Maigue. Estimates from the salmon counter installed at Adare show that in 2015, the most recent year for which figures are available, 1200 salmon returned to spawn in the Maigue catchment. This not regarded as sufficient to produce a salmon population that could be harvested commercially or by angling, and consequently, the Maigue is currently closed to salmon fishing. Given the size of the catchment and other factors, it is estimated that an excess of 4,600 salmon (the conservation limit) would need to return to the Maigue annually in order to produce a surplus of fish that could be harvested. The conservation limit is the number of spawning salmon salmon needed to produce the next generation of salmon. If the number of spawning salmon in a river consistently drops below the conservation limit because of low numbers returning or over-fishing, then the population will dwindle and may eventually face extinction. (One way of thinking of the conservation limit is the amount of seed a farmer retains from a crop to plant a crop the following year; if he doesn’t retain enough or consumes some of it, then he will not have enough to plant all his land the following year, and his harvest will diminish).

One of the aims of the Maigue Rivers Trust is to work, in cooperation with state agencies and other bodies, towards the restoration of a sustainable recreational salmon fishery in the Maigue catchment. Whether this is achievable or not depends on understanding and counteracting the factors that have caused the salmon decline. Foremost of these are: how well the salmon are surviving at sea; water quality in their spawning rivers, barriers to migration such as weirs and dams; overexploitation and illegal fishing. Currently, the survival of salmon at sea is very poor. Prior to 1996, estimates of marine survival rates generally exceeded 15%; i.e. for every 100 smolts that went to sea from Irish rivers, 15 returned to spawn as adults. Since then however, marine survival has declined just above 5%. The reasons for this decline are not clear but may be related to changes in the salmon’s feeding patterns at sea caused by climate change. Against this background, it is essential to maximize the number of young salmon smolts returning to sea. Removal of migration barriers and prevention of illegal fishing are important, but in the Maigue catchment water quality is more critical. Salmon need very good water quality for spawning and for growth and survival of when young. Juvenile salmon are scarce or absent from the upper part of the Maigue, the upper Camoge tributaries and Glosha and Barnakyle rivers where poor water quality makes the water body unfavourable for salmon survival. Restoration of spawning habitat and good water quality is essential for the future of salmon in the Maigue catchment.

Brown Trout

Brown trout are the most common and abundant large fish in the catchment. Brown trout live in all catchments in Ireland, provided the water quality is suitable and there are spawning areas. Like salmon, trout require very good water quality. They are present in the main channel and tributaries but are absent or scarce in much of the Maigue headwaters and in some of the tributaries, probably because of poor water quality there. Trout grow very fast in most of the rivers of the Maigue catchment. The Maigue was regarded as one of Ireland’s premier trout angling rivers up until the start of an arterial drainage scheme in the 1970s, which brought many benefits, but also heralded a decline in the river habitat and fishery. Poor water quality in the 1990s also had a negative impact on trout and salmon. Much work has been done in the catchment to restore the river habitat in order to enhance the spawning of trout and salmon, but water quality is still an obstacle to further improvement in many parts of the catchment.

Sea trout are a migratory sea-feeding form of brown trout that are mainly confined to the poor acidic rivers of the west and north-west (Went 1964), but there have been reports of sea trout in the Maigue. So called “slob trout”, or brown trout that live in the brackish tidal waters of estuaries, can be found downstream of Adare.

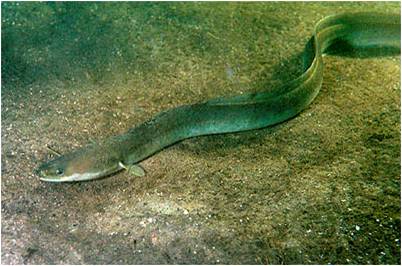

European Eel

European eels, like salmon, are migratory fish. He adults spend most of their lives in rivers and lakes, and when they are mature, they descend to the sea. They migrate to spawn in the Sargasso sea off the east coast of the U.S. a distance of over 5,000 km. Eel larvae are carried by the Gulf stream back to European coasts and grow into “glass eels”. This journey can take up to 3 years. In European coastal waters, they grow into juveniles “elvers” that ascend rivers in large numbers in late spring and early summer. Dams and weirs are obstacles to the migration of elvers and are probably one of the reasons for dramatic decline in eel populations across Europe (up to 90%) since the 1970s. The European eel is classified as critically endangered in Ireland and other European counties, and is the most threatened native fish species. Eels are widely distributed in the Maigue catchment where there were eel fisheries here in the past. The Civil Survey of the mid 17th century mentions the presence of up to 8 eel weirs on the Camoge between the Maigue confluence and Dunkip (Went, 1960).

Table 1. Fish species recorded in the Maigue catchment.

|

Fish species |

Maigue Estuary |

Rivers |

|

Brook Lamprey Lampetra planeri* |

|

√ |

|

Brown Trout Salmo trutta |

√ |

√ |

|

Common Goby Pomatoschistus microps |

√ |

|

|

1Dace Leuciscus leuciscus |

√ |

√ |

|

Eel Anguilla anguilla |

√ |

√ |

|

Flounder Platichthys flesus |

|

√ |

|

Greater Pipefish Syngnathus acus |

√ |

|

|

1Minnow Phoxinus phoxinus |

√ |

√ |

|

1Perch Perca fluviatilis |

√ |

√ |

|

River Lamprey Lampetra fluviatilis* |

√ |

√ |

|

Salmon Salmo salar |

|

√ |

|

Sea Bass Dicentrarchus labrax |

√ |

|

|

Smelt Osmerus eperlanus |

√ |

|

|

Sprat Sprattus sprattus |

√ |

|

|

1Stoneloach Barbatula barbatula |

|

√ |

|

Thick Lipped Grey Mullet Chelon labrosus |

√ |

|

|

Three-Spined Stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus |

√ |

√ |

1Non native species in Ireland, introduced sometime after the 12th century

Lampreys

Two species of lamprey are found in the Maigue catchment: brook lamprey and river lamprey. Sea lamprey, which spawns in the lower Shannon and Mulkear river, have not been recorded from the Maigue system. Lampreys are primitive eel-like fish. Sea lamprey and river lamprey are parasites of fish to which they attach by means of a sucker-like mouth. Brook lampreys, the smallest of the three lampreys, are non parasitic.

Perch, Pike and Rudd

Perch and flounder are found only in the Clonshire River. Pike, a large predatory fish, were not recorded in a 2103 river survey, but there are anecdotal reports of them occurring in the slower reaches of the Camoge. The 17th century Civil Survey refers to a weir at Mainistir where eels and pike were trapped. Pike are regarded as an introduced species, and this is one of the earliest references to their occurrence in Ireland. Lough Gur, the largest lake in the catchment, also contain, perch and pike, eel and large populations of rudd. Charles Dineley, who travelled around Ireland in the first half of the 17th century, visited L. Gur and remarked “The Lough aboundeth in fishes, pikes eels and roches in vast quantity”. The “roches” were almost certainly rudd, a native species; roach were introduced to Ireland in the 19th century. Perch and pike are reputed to occur in L. Nagirra. Dromore Lough contains rudd and pike. Bleach Lough is a trout fishery managed by Bleach Lough Anglers who stock it with brown and rainbow trout. Perch, rudd, roach and pike are also found in the lake (http://www.bleachloughanglers.ie). None of the lakes in the catchment have feeder streams with suitable spawning habitat for brown trout or salmon, so these fish do not naturally occur in these lakes.

Sticklebacks, Stoneloach and Minnow

These are small fish that are common in the Maigue catchment. Collectively they may be known as (pinkeens”). Minnows and stoneloach are introduced species. Minnows and sticklebacks often form small shoals. They are frequent prey of larger fish such as trout and perch.

Dace

Dace are a non-native and invasive species first recorded in the R. Maigue near Adare Manor by electro-fishing in 2004. It is surmised that the Maigue may have been colonized by migrants from the Ahaclare R., which drains Doon Lough in Co. Clare and which flows into the Shannon Estuary opposite the Maigue Estuary. Up to their discovery downstream of Doon Lough in 1980, dace were unknown in Ireland except for the R. Blackwater, into which they had been accidently introduced by anglers in 1889. Dace are also found in the Lower Shannon and Mulkear. In the River Barrow, where they were first reported in 1994, dace have spread upstream and large populations now occupy 69 km of the river channel. They were not recorded in a survey of the catchment upstream of Adare in 2013. This suggests that dace have not spread upstream of Adare, but further surveys are needed to confirm this.

Crayfish

Cray are not fish, but freshwater crustaceans related to lobsters. White–clawed crayfish (Austropotamobius pallipes), Ireland’s only native crayfish, are widely distributed in the main channel of the Maigue and in the larger tributaries, but were absent or scarce in the smaller tributaries. Crayfish are a keystone aquatic invertebrate in limestone rivers and lakes, and are an important food item for fish, especially trout and eels. White-clawed crayfish are protected in Ireland under the Wildlife Act. The species has been declining rapidly in its main European range under the impacts of introduced non-native crayfish species, crayfish plague (an introduced fungal disease), and deteriorating water quality. Although declines have occurred here as well, the Irish populations are still fairly robust, and in a conservation context they are of international importance.